Peter Swanton is using Indigenous knowledge to study the stars

For generations, Indigenous knowledge of the stars has been shared through storytelling, dances, songs and other oral traditions.

As a PhD scholar, Peter Swanton is exploring how this knowledge can be used in contemporary stargazing and science.

“I look at the ways our mobs and our communities have looked at the stars for tens of thousands of years, and how we can apply that knowledge to how we do astronomy and astrophysics in Western academia today,” he explains.

The Gamilaraay/Yuwaalaraay man took a wandering path to reach the Mount Stromlo Observatory at The Australian National University (ANU).

After exploring a variety of career paths – from hauling sugar cane and selling automotive parts at a smash repair shop to working as a nightclub bouncer and tutoring Indigenous students in maths and science – Swanton decided to try university.

It was during a science and engineering bridging course that he met physics lecturer John Daicopoulos.

Daicopoulos, who was pursuing a master’s in astronomy and astrophysics, became a guiding star to Swanton, inspiring him to leave the temperate North Queensland winter for ANU and Canberra’s chilly climes.

Seeing knowledge in the sky

Part of Swanton’s research is about finding ways to protect the night sky from light pollution and space junk. The clearer the sky, the better able we are to preserve Indigenous knowledge of the cosmos.

Such knowledge is particularly valuable when it comes to ‘transient events’ – astrological occurrences that are only visible for select periods of time, such as eclipses and supernovas (aka powerful star explosions).

“In the Milky Way, we would expect a supernova about every 100 years, but the last one that went off in the night sky was 1604 – Kepler’s Supernova. We’re about 300 or so years overdue for another,” Swanton says.

“We can’t go back in time and see them. But supernovae leave remnants, an aftermath, and we can actually get valuable information from viewing those with modern telescopes.

“If we have historic records of supernova from people that have observed the stars for tens of thousands of years, we can then go and point our telescope in the right direction.”

Swanton points to a 4th century Chinese astronomer who recorded the appearance of a new star, which is now believed to have been a supernova called SN 393 at the tail-end of the Scorpio constellation. Having documentation of this sighting enabled Chinese astronomers to discover the remnants of the supernova almost 1,700 years later.

“There’s evidence to suggest that the Yolgnu Matha people, up in East Arnhem Land, actually saw SN 393 as well and recorded that within their traditions, in a story they call the fisherman brothers’ story,” Swanton says.

Passing on the expertise

Journal article and research papers are far from the only means of documenting our learnings about the world around us.

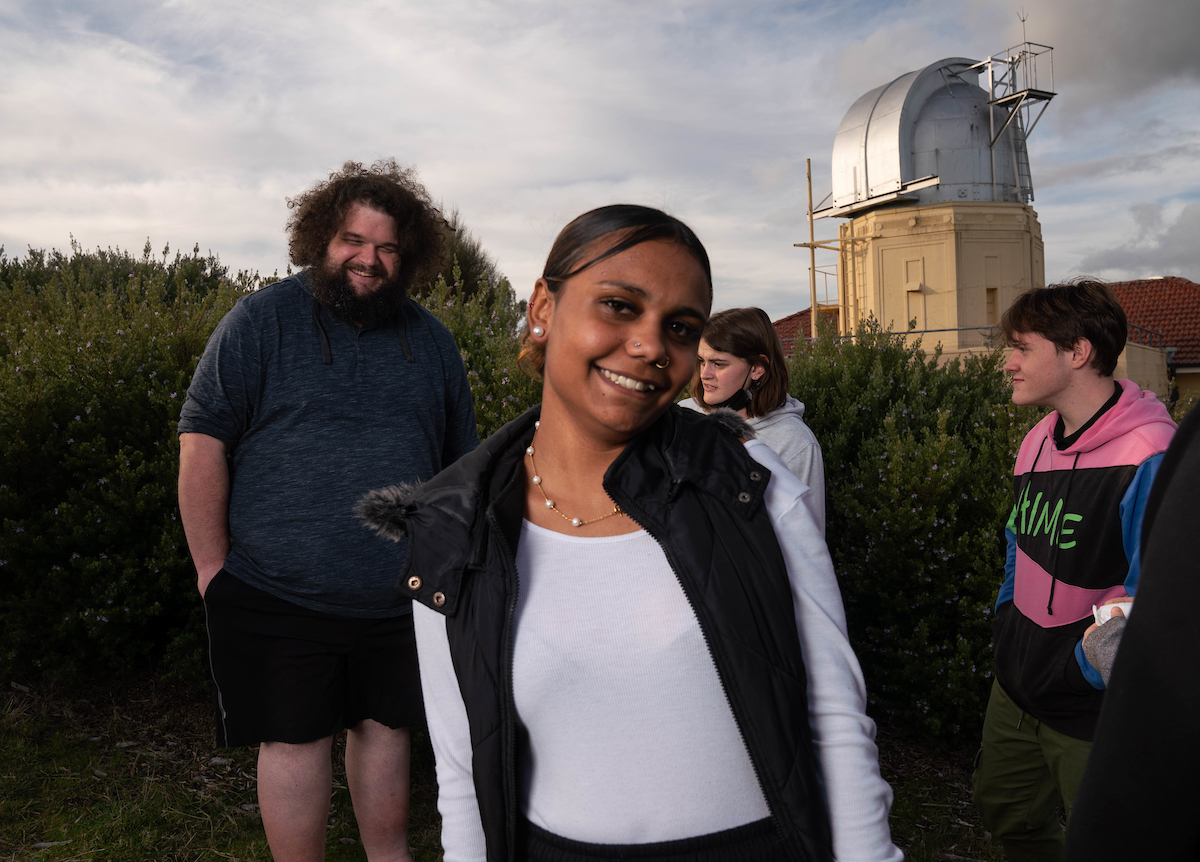

Swanton has taken a number of approaches to sharing knowledge, including holding public Indigenous stargazing events, leading work experience programsfor Indigenous high schoolers and delivering telescopes to regional kids.

“A lot of the work I do is to show our young, Indigenous, next generation of kids, that our knowledges are significant and they are very much an integral part of understanding the world we live in,” Swanton says.

“There’s far more work than I could do in a PhD than needs to be done, and we need to be encouraging Indigenous people to be the ones leading the way in researching and doing work in this space, and in Indigenous knowledges as a whole.

“At the end of the day, what we do in science is a journey of understanding our place in the universe and how things work.”

Swanton’s outreach work also has another purpose – it enables him to be mentor and teacher for young Indigenous students – just as his physics lecturer was for him.

“I always wonder if I had someone like me coming to my school and talking to me, then maybe it wouldn’t have taken me 10 to 11 years after high school to find the thing I was interested in,” Swanton says.

“It might have been a case of me finding what I what I was looking for earlier – someone might have encouraged me to do physics in high school.

“I avoided it because people said it was hard. Turns out, I’m pretty good at it.”

This article was first published in ANU Reporter.